Imagine for a moment that you are implementing a five-year program to increase income for farmers. You have done all the hard work:

– designed the program based on consultations and learning from the past,

– raised adequate resources for the implementation,

– worked with local partners whom communities trust,

– established good monitoring and learning systems making adjustments as you go along.

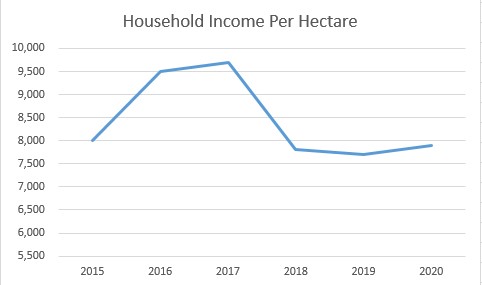

At the end of the five-year period, this is what your data tells you.

Rather than increasing over the project implementation, the household income per hectare has actually reduced substantially after increasing for the first two years. Your analysis shows that there was a drought in 2017 which accounted for the drop that year. A shock from which farmers did not recover.

When you see this, what inferences might you draw about the success of your project. Would you, in all honesty, be able to argue that the resources invested were not wasted? Would you be able to sell this argument to others?

Think about what your response might be before you read on.

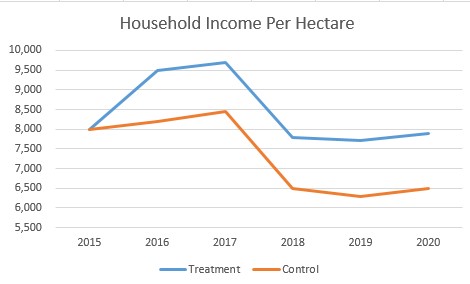

Now imagine that right at the outset, you had wanted to know about the impact your project created. You wanted to be sure that you would be able to attribute the impact you saw to your project. That you wanted to eliminate all other probable causes that might have an effect on your key outcome area – change in income for farming households. That you had invested in tracking income in communities where your project was not being implemented. Now suppose you plotted income from your project area and the area where you were not implementing and this is what you saw:

The blue line represents the income from the area you implemented your project in. The orange line is the income from another area where the project was not implemented.

Now what would your inferences be?

Would you say:

Household Income in the project area has not increased as was envisaged. However, if there had been no project being implemented, farmers would have been worse off. This seems to indicate that the project interventions helped in initially raising income, and then mitigating the impact of the shock experienced by farming communities and markets. This means that the project did deliver positive impact, if not the one that had been envisaged at the design stage.

What has happened is that because of your additional investment, you have been able to answer the question – “What if we had not intervened? What then would have been the income of farmers?”. In technical terms, you have raised and answered a counterfactual. You are now able to understand and explain the consequences of alternative choices you might have made; in this case not intervening at all.

If this is the case, why don’t all projects do this? There are many reasons for that. In no particular order they include,

- Most projects do not seek attributability of outcomes or impact and hence there is no need to establish a counterfactual.

- You need to be able to establish a counterfactual and that is not always possible. For instance, you cannot answer the question “What if the Allies had not won WWII?” Anything that you might say, will belong to the realm of conjecture, even fiction.

- The area in which you gather data without intervening, called the control area in Randomised Control Trials, needs to be very similar to the intervention area. This is more readily possible in clinical trials but is not always easy to achieve in projects working in communities. For instance, it is not necessarily enough to say “I am implementing in xx villages, I will take some other villages as the control area.” The characteristics of the villages in both sets need to be similar – size, economies, nearness to large urban centres / highways, etc.

- Gathering data in an area you do not intervene in is resource intensive and many projects just do not have these available. This is especially so because the size of the control area where data is gathered needs to be similar to the intervention area. One cannot intervene with a population of 100,000 and have 10 people as meaningful control.

- There are ethical considerations related to observing and capturing data without intervening even in difficult circumstances. I remember working on a program where we were trying to establish a baseline for child mortality. It was important to be able to do that before replicating an intervention that had been successful elsewhere. We were testing whether technical interventions and social capital could be transferred across communities in order to make an assessment of whether the intervention that was successful in a small area could be taken to scale. This meant that despite knowing about some intervention that may help, we were unable to intervene, but had to continue to simply gather data. In this case, it meant that a child might die which we did not do anything.

To conclude, to be able to attribute change to one’s interventions, one needs to be able to get rid of the impact of other factors that may have affected, environmental noise. The most effective way of doing it is by establishing a counterfactual.

Makarand

This post is part of a series that I want to write where I attempt to demystify jargon that we use in the development world. You will get to see a list of topics I have identified here. The hyperlinks, where available, take you to the posts on the topic.